Japan Brings its Artisanal Food Culture to NYC

While the American food world has become fascinated by the wide-ranging health benefits of fermented foods, the value of fermentation is not news to Japanese food artisans. For millennia, Japanese foodways have centered flavor profiles created by fermentation. In fact, much of Japan’s national cuisine is rooted in a few key ingredients, all fermented: shoyu (or soy), miso, mirin, and sake. Linking these diverse products is a single organism, koji mold (or, Aspergillus oryzae), that feeds on grain—particularly, rice, soy, and barley. Given its foundational position in the flavors of Japan, koji mold is prized as Japan’s “national fungus.”

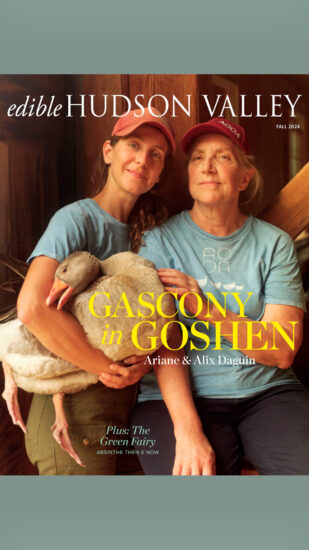

With Taste of Japan, a campaign launched by Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), New Yorkers will have a rare opportunity to experience the rich history of artisanal Japanese fermentation. With the support of JETRO (the Japan External Trade Organization), several of the City’s most prominent Japan-focused restaurants—Sushi Nakazawa, Ramen Nakamura, Blue Ribbon Sushi Bar and many others—will showcase a wide variety of Japan’s artisanal fermented products on their menus. At Go-Go Curry, you’ll find katsu curry served with natto, or sticky, umami-rich fermented soybeans; at Sakagura, look for grilled cod marinated in tahini and Dassai sake kasu (kasu is the lees generated by sake production). And, on September 21, Japan’s MAFF brought several prominent Japanese food artisans to Carnegie Hall for The Richness of Fermentation, a seminar that explored fermentation’s role in Japanese culture and cuisine. Highlights included a discussion of fermentation in the history of sushi led by Hirotoshi Ogawa, the Japanese Cuisine Goodwill Ambassador, and presentations on artisanal shoyu by Taisuke Ninagawa (Director, Nitto Brewery Corporation) and Youichi Yugeta (President, Yugeta Shoyu LTD).

While establishing fermentation’s place in Japanese history and cuisine, The Richness of Fermentation also explored the current state of Japan’s food traditions. Few Americans realize that the centuries old technique of brewing kioke soy sauce—that is, soy sauce fermented in kiokes, traditional cedar casks that have been naturally colonized by ambient yeasts and bacteria—represents fewer than 1% of the soy sauces available on the market today. In fact, the traditional process has been so thoroughly replaced by modern techniques using plastic and steel fermentation vessels that the artisans making traditional kiokes have dwindled to just one producer, and there are fewer than 4000 kiokes in use today. This loss is great, as traditional kioke fermentation techniques—analogous to aging wine and whiskey in barrels—yield complex flavors that can’t be achieved in steel or plastic tanks. The Kioke Shoyu Export Facilitation Consortium was formed to raise awareness of Japan’s vanishing kioke tradition, and to introduce new audiences to the subtle flavors of kioke shoyu.

Along with raising awareness of kioke shoyu, the seminar presented the wide spectrum of Japanese soy sauce styles generally invisible to American consumers. The all-purpose soy sauce style on American shelves, koikuchi, lands in the middle range of aging time and flavor intensity. However, shiro and usukuchi shoyus are young, subtle, lightly colored soy sauces best used with mildly flavored raw fish or white fried rice; on the other side of the spectrum, richly colored saishikomi and tamari deliver intense, complex flavors.

While shoyu is the most recognized of Japan’s exported ferments, koji mold is also behind that nation’s celebrated beverages. When rice is inoculated with koji mold, the result could be spun into miso—but, through different artisanal processes, that basic fermentation can also yield shochu (a distilled beverage), sake, rice vinegar and mirin. The processes that create these diverse beverages and their unique flavors have been refined by Japanese artisans over centuries, with the first recorded mention of sake being in the 8th-Century AD (several hundred years before whiskey enters the written record). Since that time, distillers have continually shaped traditional processes to produce the distinct flavors of the artisanal shochus, sakes, and mirins on the market today.

If you’d like to experience the diversity of Japan’s fermentation culture here in New York City, visit Taste of Japan.

Check out the full list of participating New York restaurants below and be sure to visit by Tuesday, September 27th to try their featured Japanese fermented dishes!

All images courtesy of MAFF